Proletarian Ecology: On the Origins of Capitalism

Brief: Climate Vanguard, 29 July 2023

Capitalism is driving Earth systems collapse. If we are to take seriously the task of ending capitalism and salvaging a habitable future, then we must develop an understanding of the historical transition to capitalism. This is a first step in distilling an anti-capitalist theory that can inform revolutionary practice. In this brief, we will provide an ecological perspective on capitalism’s creation story.

Labour

For the vast majority of human history, people have met their material needs by directly engaging with nature. For example, people gathered food from the forest to feed themselves and their community.

Importantly, this material relationship between humans and nature is mediated through labour. In Capital Volume 1, Karl Marx defines labour as a “process by which [a person], through [their] own actions, mediates, regulates and controls the metabolism between [themselves] and nature” (Marx 1976). Before capitalism, interacting with nature was “a purposeful activity aimed at the production of use-values,” in other words, “an appropriation of what exists in nature for the requirements of [humanity]” (Marx 1976).

-

A use-value is a thing that carries useful qualities. For example, a farmer might grow an apple because they like its sweet taste or because they’re hungry.

With the rise of civilisation, humanity was split into two classes: one class that worked the land and another that appropriated the labour of others (Wood 2017). This class structure had an impact on society’s interaction with nature (Saito 2023). To understand this particular impact under capitalism, let’s first explore how it looked under feudalism, the mode of production before capitalism.

-

A mode of production consists of the “relations of production” and the “productive forces.” The relations of production refer to how classes relate in the production process. For example, under capitalism, a specific mode of production in history, the relations of production are defined by the capitalist class exploiting the working class. The productive forces refer to the productive capacity of humanity, which is enabled by tools, machines, factories, and other technology.

Feudalism

Under feudalism, the class that worked the land were serfs and the class that appropriated their labour were lords. Broadly speaking, lords gave serfs a plot of land and protection in exchange for the goods and services they produced, which were appropriated through force.

While feudalism was an “enormous burden” for masses of people, it redefined the class structure more favourably than the slave system under imperial Rome, the previous mode of production (Federici 2004).

Key was that people had access to their own plot of land, providing “direct access to the means of their reproduction” (Federici 2004). Moreover, people had access to the commons, such as meadows, forests, lakes, and wild pastures, providing an additional layer of material security (Federici 2004).

-

The means of reproduction are things that are necessary to keep people alive and bring new life into the world, such as housing, food, and energy.

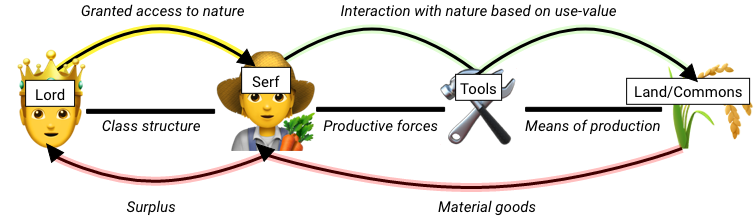

Figure 1: The feudal mode of production.

In Figure 1, we can see how the feudal class structure impacted humanity’s interaction with nature. More specifically, since people had access to the land and the commons, they could produce for use-value. Breaking this access to the land and the commons was instrumental in the creation of capitalism.

Primitive Accumulation

In the mid-14th century, the Black Death killed up to 40% of the European population. The resulting labour shortage strengthened the hand of the serfs, who no longer were threatened by expulsion from their lands. Through militant organising, including insurrections and rebellions, serfs were able to increase their quality of life (Federici 2004). For example, in England, serfs enjoyed high wages, cheap food, and other ‘luxuries’ like employers paying for travel to and from the worksite (Federici 2004). Marx dubbed this period “the golden age of the European proletariat” (Marx 1976).

However, the serfs' radical social experiment would not live long. Suffering from “chronic disaccumulation,” European elites plotted a “counter-revolution” (Federici 2004). Beginning in the late-15th century, European elites began to privatise serfs’ lands and the commons. In England, this was primarily accomplished through “enclosure,” a process of mass land theft and dispossession by the landlord class (Federici 2004).

Meanwhile, in the Global South, European colonisers enslaved 5 million Indigenous Americans and shipped 15 million Africans across the Atlantic. They were put to work extracting gold and silver and harvesting cash crops (e.g. sugar), wealth which flowed back to European shores and fueled the emerging capitalist mode of production (Hickel 2020).

Marx calls this “primitive accumulation,” a “historical process of divorcing the producer of the means of production,” primarily the land and commons that people depended on for survival (Marx 1976). In other words, access to nature. Indeed, Marx makes repeated mention of people no longer being “bound to the soil” (Marx 1976).

-

The means of production are things that are required for production, such as land, raw materials, tools, machines, factory buildings, and energy.

Contrary to what’s taught in school, primitive accumulation and the transition to capitalism was not peaceful. Masses of people were “systemically hunted and rooted out” of their lands through enclosure and colonisation (Marx 1976). Befitting this age of brutal violence, historians have called it “the Iron Age,” the “Age of Plunder," the "Age of the Whip,” or with Marx, not one to mince words, “ruthless terrorism” (Federici 2004; Marx 1976).

The Birth of Capitalism

Primitive accumulation left serfs dispossessed of their lands and cut off from the commons. All of a sudden, the only thing they had left was their own labour power (i.e. the capacity to work). In order to survive, people were forced to sell their labour power to an emergent capitalist class (i.e. wage-labour), which now maintained exclusive ownership over the means of production via private property – the most important being the land and commons which serfs had relied on.

It is important to note two things here. First, in the Global South, people were primarily enslaved, as opposed to being forced into wage-labour. Capitalism is a mode of production defined by wage-labour, not slave-labour. Thus, capitalism originated in Europe and not in the Global South. That being said, slave-powered resource extraction was undoubtedly key to the development of European capitalism. Indeed, capitalism depends on non-capitalist modes of production for its existence, a central antagonism, but one beyond the scope of this brief.

Second, it was predominantly men who were forced into wage-labour. Women, on the other hand, were forced into the reproductive labour of raising children and keeping the workforce alive. Under capitalism, reproductive labour is not waged, which means women became entirely dependent on men and their wage-earning to stay alive in a market society, also known as the “patriarchy of the wage” (Federici 2004).

Thus marks the violent beginnings of capitalism, “when great masses of men are suddenly and forcibly torn from their means of subsistence, and hurled onto the labour-market as free, unprotected and rightless proletarians” (Marx 1976). Those who resisted proletarianisation became beggars, robbers, and vagabonds. Their resistance, however, was viciously suppressed through “bloody laws,” including capital punishment (Marx 1976). Under the reign of Henry VIII, 72,000 vagabonds were hanged (Hickel 2020).

-

Traditionally, the proletariat, also known as the working class, are people who sell their labour power for a wage. We believe this traditional understanding of the working class must be expanded to include a multi-racial global coalition of the “informal proletariat” residing in urban slums, women engaging in unpaid care work, and indigenous people providing vital metabolic labour (e.g. ecological restoration).

Meanwhile, land and the commons, now under private control by the capitalist class, were developed for a very novel purpose: profit. For example, capitalists began turning arable land into pasture for sheep farming because it was profitable to do so (Wood 2017). George Monbiot describes how these “woolly maggots” “sheepwrecked” the British countryside by compacting the land and eroding the soil, preventing the necessary tree growth to prevent landslides and flash flooding (Monbiot 2013).

Here we can begin to see how humanity’s interaction with nature underwent dramatic changes. No longer was it governed by the production of use-values, but by exchange-value and capital accumulation.

Figure 2: The capitalist mode of production.

-

Exchange-value is the proportion in which one commodity is exchanged for another commodity. For example, a bicycle is exchanged for $100 (also known as the money commodity). Capitalists buy the means of production and human labour power (M) in order to produce a commodity (C) which they then sell for a profit (M') in the process of exchange (C-M'). The resulting profit (M') is then re-invested to produce more commodities (C') which are sold for more profit (M''). This ceaseless process is known as capital accumulation.

As Figure 2 shows, this is due to the emergence of capitalist class relations, specifically a landless proletariat forced to sell its labour power to capitalists who re-oriented production for the sole purpose of exchange-value and capital accumulation. And, as we can see in the “sheepwrecked” example, this process of capitalist “class making” sowed the seed of ecological destruction, which continues to push planetary systems to the brink of collapse (Barca 2020).

Proletarian Ecology

Fast-forward 500 years, and our society is still split into two classes: the working class and the capitalist class. The working class remains alienated from nature and the ecological means of survival. Instead of meeting their material needs through their own land and access to the commons, they’re forced to sell their labour power to the capitalist class in exchange for money, which is used to purchase commodities on the market necessary for survival (housing, food, energy) (Huber 2022).

Matthew Huber defines this “profound alienation from the ecological conditions of life itself” as “proletarian ecology” (Huber 2022). Crucially, Huber makes the assessment that for the working class, which is composed of the vast majority of humanity, “the main threat to their livelihood is the market itself” (Huber 2022).

This means that most people will experience the biting impacts of climate and ecological breakdown through the market, such as heatwaves that make outdoor work unbearable and drought-induced crop failure that sends food prices surging and forces smallholder farmers into the overcrowded urban labour market.

So, what does this mean for our organising? To end capitalism, we need a global majority, the working class, engaged in revolutionary struggle. To mobilise the working class, the climate movement must develop a politics that speaks directly to their material interests. In our Ecosocialist Program, we make the argument that this is best done through a program of decommodification.

Working people have no guaranteed access to the ecological means of survival. As we have shown, this is because they were violently torn from their lands and the commons through a process of primitive accumulation. Things like housing, food, and energy became commodities that could only be accessed through money earned from wage-labour.

A program of decommodification would not only guarantee housing, food, and energy, but also 21st century services like healthcare, education, and transport. This is a politics that improves the livelihoods of the global majority. It would make ‘climate action’ synonymous with ‘my life will get better.’ In the process, reorienting production to meet human needs within planetary boundaries, as opposed to the blind pursuit of profit and capital accumulation, would stave off irreversible Earth systems collapse.

Bibliography

Barca, Stefania. Forces of Reproduction: Notes for a Counter-Hegemonic Anthropocene. Cambridge University Press, 2020. https://www.cambridge.org/core/elements/abs/forces-of-reproduction/BE9B0DBDC 89593F3284FE3F51D3B0418.

Ellen Meiksins Wood. The Origin of Capitalism: A Longer View. London: Verso, 2017. Federici, Silvia. Caliban and the Witch: Women, the Body and Primitive Accumulation. New York: Autonomedia, 2004.

Hickel, Jason. Less Is More: How Degrowth Will Save the World. London: Windmill Books, 2020.

Huber, Matthew. Climate Change as Class War: Building Socialism on a Warming Planet. London: Verso, 2022.

Marx, Karl. Capital Volume 1. Penguin, 1976.

Monbiot, George. “Sheepwrecked.” George Monbiot, May 30, 2013. https://www.monbiot.com/2013/05/30/sheepwrecked/.

Saito, Kohei. Marx in the Anthropocene. Cambridge University Press, 2023.